I had my first sports-related blood analysis in February 2016. I maintain a comprehensive table of blood analyses, so I know that over the past eight years, I have given blood for analysis a whopping 66 times, with a total of 86 different blood markers determined. Through blood analysis, I assess the impact of training and ultrasport on my body, whether my diet provides all the necessary nutrients, how my body recovers from trainings, and which foods best help achieve this. Understanding how my body functions has been greatly aided by blood analyses.

This post is a continuation of the February 9th post on nutition. Today, I will discuss the results of the blood analysis conducted on February 2nd, which allows me to see how the foods described in the nutrition post are reflected in my blood picture and aid in recovery from training. In the previous post, I wrote about how much energy training and ultra long challenges demand from my body and how my diet meets those needs. I also wrote about the misconception, as if a lot of sports and a normal body weight would allow me to watch my diet through my fingers.

But now, onto the blood analyses. To provide a better overview, I group the blood markers into three categories. Firstly, blood markers that I primarily use to assess whether my dietary preferences (i.e. whole plant-based foods) provide all the necessary nutrients for my body. Then, I discuss blood markers by which I assess the effects of my sport endeavours on my body and try to identify potential problems proactively. Lastly, I address blood markers by which I assess the stress induced by training, its magnitude, and the rate of recovery.

Photo: Jakob Meier

Blood Markers Related to My Dietary Preferences

I am a big fan of whole plant-based foods. Approximately 98% of my diet consists plants. To prevent B12 deficiency, I take it as a supplement. Once a year, I check that it provides me with the necessary amount. There are several ways to detect B vitamin deficiency. Firstly, of course, the vitamin B12 analysis itself. However, there are also cases where this analysis is within the reference value, but the body may still be deficient, or where it is below normal value, but there is actually no deficiency in the body. In such cases, if there is suspicion of B12 deficiency, it is worth measuring the active form of vitamin B12 or doing a homocysteine analysis. Since the symptom of vitamin B12 deficiency is, among other things, extreme fatigue and lack of energy, which are also characteristic of iron deficiency, I occasionally do a homocysteine analysis instead of a B12 analysis or have it determined in its active form.

Due to my sports activities, I consume twice as much food as usual, so I keep an eye on markers that assess cardiovascular health. These include HDL and LDL cholesterol and triglycerides. I have been monitoring them for a long time, and so far, they have always been in good order. Here, I must thank plant-based food.

Identifying the effects of heavy exercise

I carefully monitor blood markers that help detect iron deficiency. My iron levels have always been low (even when I was still eating animal products), but for the past five years, this blood marker has been below the lower reference value. Currently, I have reason to believe that running plays a significant role in this. Five years ago also marks the time when my annual running mileage increased to six thousand kilometers or more. Together with my physician, I have been searching for solutions all this time, and thus, I have become aware of various blood markers that, together, help me assess the actual situation.

As far as I understand, ferritin analysis is where I should start. If ferritin is normal, then it is likely that iron levels are good. However, if the ferritin indicator drops below normal value, it is a sign that iron reserves are depleted, but this does not necessarily mean that the body is iron deficient. Then other blood markers come into play to detect whether there is a disturbance in iron availability, deficiency, etc. So when giving blood, in addition to ferritin, I also have the following analyses performed: complete blood count, iron, transferrin and its saturation, and transferrin soluble receptors. The latter allows assessing the need for iron at the cellular level. In case of iron deficiency, the content of transferrin is increased, and at the same time, the saturation of transferrin is decreased. Hematocrit values indicate low iron levels, with low values of hemoglobin, erythrocytes, hematocrit, MCV, and MCH.

My latest blood test showed a low ferritin level (12.3 µg/l), but all other aforementioned markers did not indicate iron deficiency. So, it seems that there is no deficiency in the body at the moment, but at the same time, there are no reserves that could be used if necessary. Fortunately, I have learned to recognize the symptoms of iron deficiency (such as fatigue and weakness, and the ability to tolerate intense workouts). When these symptoms occur and I check the blood, often the ferritin and other markers mentioned above show a clear sign of iron deficiency.

Another important indicator is vitamin D, which requires regular monitoring due to extensive sports activities. This vitamin plays a significant role in athletic performance. My measurements and observations indicate that the demand for and consumption of vitamin D increase with extensive running training. Fortunately, my vitamin D is well under control. For example, in the last two years, my vitamin D level has been over one hundred, ranging from 106 to 147.

Extensive sports also mean a lot of sweating. Since I exercise a lot indoors, this also amplifies sweating. For example, when running a marathon on a treadmill, I have to change my t-shirt six times because otherwise sweat would flow into my running shoes and cause significant blisters. Therefore, I also keep an eye on sodium, magnesium, potassium, and calcium levels. These indicators remain in good order. I do not take magnesium supplements. My experience tells me that if I experience cramps during exercise, it is because I demand significantly more from my body than I prepared for with training. The last time I had to deal with muscle cramps was during the last kilomoeters of Tartu city marathon, when the muscles had clearly received so much beating that they never experience during training. The solution was to adjust the pace slightly, and the problem subsided.

Photo: Jakob Meier

A few years ago, I became aware of blood markers such as NT-proBNP and troponin I (highly sensitive), which help assess the work and condition of the heart muscles. Since my sports activities are sometimes very extreme, I have started to determine these blood markers within the scope of my challenges. So far, there have been no signs of concern.

Assessment of Stress and Recovery from Training

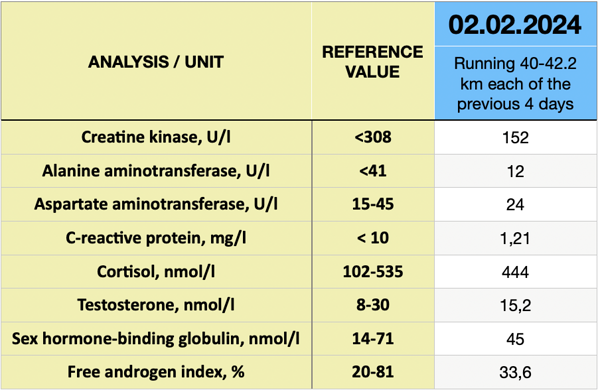

Over time, I have identified five to six blood markers that I use regularly to assess the impact of exercise during training periods and the speed of recovery. These include creatine kinase, aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT), alanine aminotransferase (ALAT), C-reactive protein (CRP), cortisol, and testosterone along with the free androgen index. Creatine kinase marker should be determined alongside ASAT and ALAT markers for assessing muscle damage. A creatine kinase value several times higher than the normal range along with high ALAT and ASAT readings indicate significant muscle strain. Conversely, elevated ALAT and ASAT levels with normal creatine kinase may indicate a liver problem.

CRP is an indicator of inflammation throughout the body – by determining this marker alone, we can detect inflammation in the body, but it does not reveal the source of the inflammation itself. However, when monitoring this marker alongside creatine kinase, ALAT, and ASAT consistently, it becomes an excellent source of information for assessing recovery. It is also useful to monitor this marker solely from a health assessment perspective to detect chronic inflammations (e.g., those caused by unhealthy diet), which over time can develop into serious health problems such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, autoimmune diseases, cancer, etc. Moreover, the determination of these markers does not entail excessive costs (see prices below).

I see cortisol and testosterone as stress markers. Cortisol is a hormone essential for many vital processes in the body. It helps control metabolism, fight infections, regulate blood sugar, and maintain blood pressure. Cortisol also plays a crucial role in preparing the body to respond to stress. Stress (including that induced by exercise) affects the amount of cortisol released into the blood. It is important to note the time of day when cortisol is measured. Cortisol levels are higher in the morning and significantly lower in the evenings.

Unlike cortisol, stress causes a decrease in testosterone levels. I have this indicator determined alongside the free androgen index (FAI), which provides an overview of testosterone levels in the free form. Free testosterone, not bound to proteins, is usable by the body. However, a low testosterone level does not automatically mean a decrease in free testosterone. For example, once my testosterone level was 15.2 nmol/l and the FAI was 33.6%. Another time (during one of my challenges), testosterone dropped to 12.5, but the FAI was higher at 34.7%.

In addition to the mentioned tests conducted during self-organized ultrachallenges, I have selectively determined blood markers such as urea, growth hormone, creatinine, insulin-like growth factor-1, reticulocyte count, and reticulocyte hemoglobin. Of course, it would be beneficial to keep an eye on them constantly, but like many of us, I operate under limited resource conditions and must make choices.

The aforementioned analyses are by no means an exhaustive list. For example, in research, in addition to the creatine kinase marker, the determination of uric acid and/or interleukin 6 markers is also used to assess the effect of specific foods (e.g., cherries, blueberries, spinach, etc.) on recovery, excessive oxidative stress, inflammation, and/or the natural killer cell count in the body. Although I have not used these two markers in assessing my recovery before and thus cannot say how they behave in my case, it hope to check them at some point in the future.

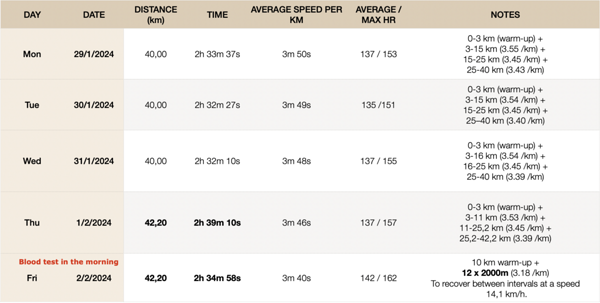

To assess stress and recovery, I give blood tests when I have already put my body under stress with training. This time, I chose the fourth week of the training cycle when I ran almost a marathon every day for five consecutive days (see table).

Just to clarify, the difficulty of running consecutive marathons is not the length, because running a marathon or a longer distance as part of training is not unusual in my case. I stress the body through speed or the combination of speed and distance. One important measure for me is how I feel the next morning. The medium intensity effort done the previous day should be gone from the body by morning. If the feeling of heaviness in the muscles has rather increased during the night (and the previous day it was not, for example, a workout that developed VO2 max capacity), then this is a sign that the exercise put a much greater stress on the body than was the goal. Rare mistakes are forgivable and the body can cope. However, if you often make the mistake of creating the right amount stress, problems will quickly arise.

So what did the blood tests show on the morning of the fifth day when I had run almost a marathon every day for four consecutive days? Exactly what my well-being confirmed. All blood markers were nicely within the normal range. Based on the results of the blood tests, a physician unfamiliar with my backround might find it difficult to guess whether or how much I exercised at all in the previous days. :).

However, I noticed two markers that indicate some effort. Had I fully recovered, my creatine kinase value would likely have been below 100, and the C-reactive protein marker would have been one notch lower (i.e., very close to zero).

High-load running workouts on consecutive days are a great opportunity to test what contribute best to quick recovery and a good feeling. On three days out of five (Mon, Wed, and Thu), I did a post-run recovery bike ride, and the next morning I felt a noticeable difference in my well-being. On those two days (Tue and Fri) when nothing followed the run, I coped well with the upcoming training sessions, but getting going required more mental willpower.

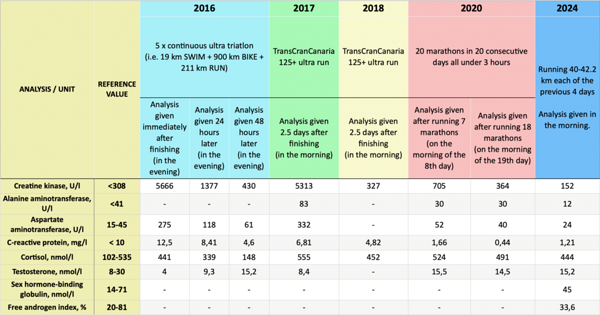

While a single analysis is always better than nothing, in assessing the size of stress caused by exercise and its recovery, the greatest benefit comes from doing it regularly and systematically. Comparison material is needed for assessment of progress. By comparing my latest analysis results with previous ones and also comparing the workouts preceding the blood test (e.g., speed, average and max heart rate, power, well-being, etc.), progress becomes quite clear. To illustrate this, I compiled a comparison table showing the imprint left by sports endeavours on me previously and how they have changed over time.

The table shows that the worst condition of my muscles, according to blood markers, was after completing my first self organized challenge (5-times continiuous ultra triathlon) in 2016. Although the normalization of blood markers occurred relatively quickly, several of them were still above normal 48 hours later. However, at that time, I had only been involved in ultra triathlons for two years, and the body was still learning and adapting to everything. Today, this challenge would leave a much, much smaller mark on the body.

For comparison, I also included in the table the blood tests given after the TransGranCanaria 125+ mountain ultra run in 2017 and 2018. In 2017, due to improper preparation, I was forced to withdraw from the run at 84 km, because my muscles were completely exhausted and refused to continue working. If I had been able to get a blood sample right after I stopped, I probably would have seen my worst creatine kinase result ever. Namely, if the analysis given 2.5 days later gave a result of 5313, one can only imagine how much higher this number would have been two days earlier. For comparison, after the 5-time continuous ultra triathlon, the creatine kinase reading had dropped from 5666 to 430 in 2 days.

I learned from my mistakes and at the 2018 TransGranCanaria ultra run (128 km and 7500 meters of elevtion) I ran my best result in this race (16:53:55). The result and great feeling were also confirmed by blood tests.

The blood profile given most recently (i.e., on February 2, 2024) is appropriate to compare with the challenge I undertook in Estonia in 2020, where I ran a marathon every day for 20 consecutive days. On average, it took me 2:52:32 to complete one marathon. During this challenge, I underwent blood analysis twice – after completing 7 marathons and then after 18 marathons (see last table above). Already in the summer of 2020, my running form and recovery were good, and running a marathon every day for consecutive days didn’t bring any big changes in the blood tests. But it turned out that there was still a lot of room for improvement – today, there is no noticeable change in blood markers.

The training cycle continued as planned for another two weeks, after which COVID paid a visit

With a week of back-to-back marathons, the training cycle wasn’t over yet. In the following, i.e., the 5th week, the focus was on cycling, including two workouts aimed at developing FTP threshold and one aimed at increasing MAP capabilities. Running, on the other hand, was significantly more modest this week – consisting of one interval session, with total weekly mileage around 100 km.

In the 6th week of training, it was time to run marathons again. This week, the key workouts included three marathons (see table), with the final one being run as an interval session. I was pleased with the speed endurance and overall feeling during these runs – the times of completing all marathons were within the range of 2:33:07-2:39:16.

The training cycle was supposed to end last week (i.e. after the seventh week) and then two easier weeks were supposed to start to rest up for the Barcelona marathon. Unfortunately, the plans had to be changed because I got sick with COVID. It was a sign that it was time to take a break. Time will tell if and how COVID affects my performance in the Barcelona marathon.

Three misconceptions regarding blood tests

Misconception #1: Blood tests are expensive

Cost is always relative. What seems expensive to one person may not be to another. Much also depends on context and values. Today, I am of the opinion that having a basic look at key blood markers once a year is not expensive. I treat this expense as an investment. For an initial overview of the main indicators, I would then order the following tests: a hemogram with a leukogram, cholesterol, vitamin D, vitamin B12, ferritin, C-reactive protein, and glycosylated hemoglobin (if I did not regularly measure my blood sugar myself). Together with blood collection service, these analyzes would cost €57.50 in Estonia. Each person can decide for themselves whether this is expensive or not.

Here I present the cost of all the tests mentioned in this post. NB! Since some tests were done some time ago, prices may have changed. Also, prices may vary slightly depending on the service provider. In addition to the cost of the tests, there is a one-time blood collection fee of €7.

Misconception #2: Trusting your gut feeling is enough

Trusting your gut feeling is worth it in many cases, but only after you’ve learned to listen to it correctly. Unfortunately, practice shows that most of the time we may not realize for months, or in some cases even years, that something is wrong with our bodies. Blood tests give us a good opportunity to peek behind the curtain and prevent potential problems from the outset. Although I have been practicing this for eight years now and have become much more skilled in understanding how blood markers react, mistakes and surprises are still not rare. So, there is still plenty of room for learning.

Misconception #3: Not being overweight means that the blood markers are also fine

It is very common to believe that if there is no overweight, there is no reason to worry. However, this is definitely not the case. The book recommended in the nutrition post discusses a study that examined normal-weight people whose daily diet consisted of a large proportion of (processed) animal foods. It turned out that despite the absence of overweight, their blood markers were very poor. So, while some of us may have a fast metabolism given to us by nature, which keeps excess weight away, it does not provide protection against the harmful effects of unhealthy food. Those whose diet consists largely of animal and highly processed foods can, for example, check via a blood marker ApoB whether and what impact this diet has had on their body. This blood marker is an additional option for assessing the risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases.

Photo: Jakob Meier

Foods I Use to Speed Up Recovery

As a conclusion to the post, I will list some foods that I like to use to reduce the impact of intensive and/or prolonged exercise on the body and to accelerate recovery from it. These are not just my subjective assessment, as their effectiveness and usefulness are confirmed by scientific research. These include blueberries, black currants, cherries, spinach, ginger, nuts, and avocado. These foods help reduce muscle pain and oxidative stress, and they have anti-inflammatory properties.

To be more specific, for example, studies have found that daily consumption of spinach alleviates oxidative stress and known markers of muscle damage. Berries are known for their good antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. For example, daily consumption of blueberries increases the number of natural killer cells, reduces oxidative stress, and increases anti-inflammatory cytokines. Similarly to blueberries, cherries are also effective in speeding up recovery from various types of exercise. Regarding ginger, it has been found that consuming 2 g of ground ginger on consecutive days helps reduce muscle pain caused by, for example, long-distance running.

Studies clearly show that the greatest benefit in terms of exercise comes from these foods when eaten regularly. Various amounts and frequencies of consumption of blueberries have been used in different hypothesis-driven studies – for example, 2 x 22.5 grams per day for six weeks or smoothies containing 200 g blueberries 5 and 10 hours before strenuous exertion and immediately, 12, and 36 hours afterwards. Regarding the daily amount of blueberries, one must experiment to see how much and how often to eat them. I usually consume about 100 g of blueberries in one day. But I have no problem eating much more of them because they are one of my favorites.

An interesting observation regarding scientific studies is that they often use foods in the form of powders, juices, and smoothies. This does not mean that these foods do not work in their natural form. This is necessary to conduct a placebo control.

These seven foods mentioned are all very beneficial and could be part of our menu regardless of the hours or minutes of sports practiced per day. Of course, there are many other similar beneficial foods that to cover them all would make this already long post book-length.